I became convinced, while watching After Earth, that it was based on a novel. I was wrong, and I’m disappointed, because this is a story that I really believe could be told more effectively in prose.

That said, it could also be told more effectively in the medium of film. After Earth underestimates its audience at some junctures, and at others seems to paint itself into a narrative corner, leaving itself with only cliches and overtly telegraphed character moments to pull it back out.

Aesthetically, the movie is lush, and presents a vision of humanity’s far-future that is paradoxically both bleak and somehow more hopeful than today. The design of space ships, architecture, and even clothing is very organic — akin to the natural-futuristic aesthetic found in films like Aeon Flux.

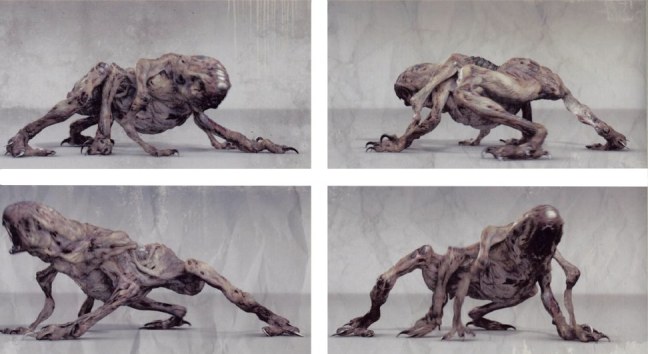

Tonally, however, this is an apocalyptic war film. We’re met with a doomed humanity, in a desperate race to save itself again annihilation by the Ursa — a breed of predatory aliens apparently designed to kill humans.

This is where the first set of questions arises.

Why are the Ursa “designed” to kill humans? Is that just a throwaway line, akin to calling them “apex predators”? Or were they actually engineered? If the latter, how, why, and by whom? Are they the natural inhabitants of the planet that humanity attempted to colonize after leaving Earth, not vicious predators at all but just regular life-forms living their own lives a la Alien?

Alas, we viewers never get those answers.

As Cypher Raige (Will Smith) and his son Kitai (Jaden Smith) crash-land on Earth we learn that the planet is now quarantined for being completely inhospitable to human life. Accoring to Smith’s character, “everything on this planet has evolved to kill humans.” On top of this, the climate has changed drastically — but not in a way that would be believably consistent with climate change. No, instead, Earth is now an evil realm in a fantasy novel where nightfall brings a literal creeping frost that descends over previously mild biospheres and freezes everything instantly, somehow without doing any long-term damage to the plant life.

It’s almost like Earth has been transformed into an elaborate training simulation meant to strengthen Earth’s military forces — which could be an interesting, Ender’s Game-esque turning point for the narrative. Unfortunately I can’t give the writers that much credit. This is just worldbuilding that tries to be cool but ends up so broken that it can barely support the narrative.

The function of the film’s technology is just as wobbly. Raige Sr., his leg wrecked, stays on board the ruins of their spacecraft while Kitai goes off in search of a rescue beacon that ended up at the crash site of the front half of the ship. Ostensibly, a combination of video and 3-D mapping technology allows Raige Sr. to observe his son from all angles at all times. But Kitai hides things from his dad at key junctures.

How much can Raige Sr. actually observe at a given time? Why does Kitai deign to hide things from his father when his father is miles away, unable to touch him, only trying to offer realistic guidance? How did Raige Sr. actually survive the crash in the first place, when the last thing we see is him being sucked out an airlock and (presumably, if we’re dealing with physics here) dumped several hundred miles away from the site where Kitai finds him?

Honestly, at this point, the story doesn’t even matter. There’s some pseudo-philosophical themes about self-control and letting go of fear, but they become so mired in the utterly nonsensical background structure of the tale that any poignancy that they would have had is totally drained.

I can’t recommend After Earth in any way, but if you’re feeling up to the task of constructing some wild fan theories to fill in those plot holes, have at it.